Did Alfred Hitchcock's Spellbound and Rebecca Influence Laurence Olivier's Hamlet?

|

Salvador Dali's set for

Spellbound's dream sequence.

Spellbound's opening title.

|

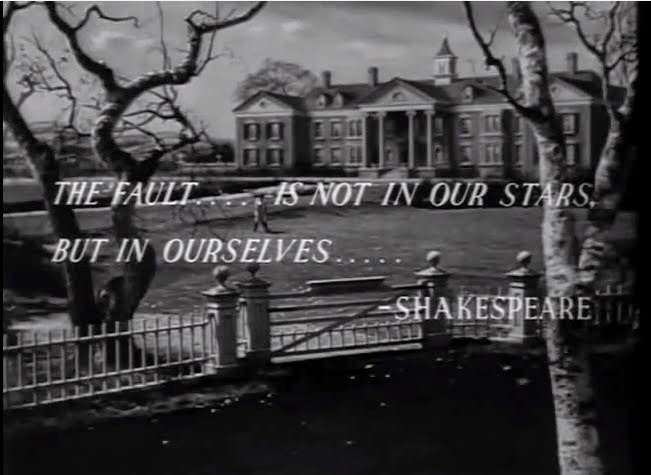

The film begins with a Shakespeare quote, a title reading "THE FAULT . . . . . IS NOT IN OUR STARS, BUT IN OURSELVES," words that come from Julius Caesar's second scene, in which Cassius tries to talk Brutus into joining the conspiracy to assassinate Caesar. Cassius tells Brutus that their present position under Caesar isn't determined by astrology—they're responsible for their own fates. This sentiment is turned upside down by the title of John Green's YA novel The Fault in Our Stars. Green's main characters are teenagers with cancer, and he uses the quote to mean that we don't control our fates. Hitchcock uses it to suggest that we're not controlled by astrology but by psychology. Behind the title's words we see the psychiatric hospital where we'll start the story, and the next, rolling titles provide us with a short, psychoanalysis-for-dummies course to prepare us for the film's use of Freudian theory.

The opening title of Olivier's Hamlet, a bit of the "mole of nature" speech (1.4.18.7-20), also prepares us for a film that has Freudian theory at its center. The title introduces the hero's "particular fault," which the film will show us is indecisiveness caused by Hamlet's Oedipus complex. The similarity between the two directors' use of their opening titles suggests an influence; if Olivier was watching Gary Cooper sea movies, then he was also watching Hitchcock mysteries. But the resemblance may simply result from the frequent, mid-twentieth-century use of opening, key-to-the-movie titles and from Freudianism's grip on many mid-twentieth-century Englishmen.

On the other hand, the opening and a key shot in Olivier's Hamlet seem very likely to have been influenced by Hitchcock's 1940 Rebecca.

Olivier played Rebecca's male lead, Maxim de Winter. In On Acting, he says that he had "a jolly time" making the film and that he admired Hitchcock as a director (262). But he never says that Hitchcock influenced him the way William Wyler did. Wyler, who directed him in the 1939 Wuthering Heights, inspired him to believe that Shakespeare could be done well on film. Before talking with Wyler, Olivier had had a low opinion of film in general and of Shakespeare films in particular, including the one he had acted in—Paul Czinner's 1936 As You Like It. Wyler told Olivier not to think that As You Like It had failed because Shakespeare couldn't be adapted to the screen:

I believe with my heart and soul that [film] is the greatest medium ever invented in the field of expression. There's nothing in literature . . . which is beyond it. If you put your mind to it. Shakespeare can be done as anybody else can be done if you just think out how. Just think and keep thinking. Do it right, and anything can be done on film. . . . [J]ust get on with getting on with your medium. (260)

|

The Chorus addresses the Globe

audience in Olivier's Henry V.

Image from Second Reel.

|

Olivier followed this advice when he made his first Shakespeare film, the 1944 Henry V, which he had originally wanted Wyler to direct. He thought hard about how to adapt the play until he discovered, to his surprise, that language of film came easily to him and that film was a natural medium for Shakespeare (On Acting 269). What had seemed "problems" in adaptation led to solutions that became some of the film's most creative moments. For example, he had wondered what to do with the play's most theatrical element, the Chorus, who speaks a prologue that specifically addresses the original audience. Olivier decided that if Shakespeare had had the Chorus address that audience, then he would do so as well, which is why the film opens in Shakespeare's time, then moves into the medieval world of the play—with detours into a fairy-tale setting for the French court scenes—before returning to the Elizabethan period at the end. These shifts of setting, perhaps the film's most distinctive feature, came about because Olivier let the play determine the film's style, rather than squeezing the play into an pre-existing style. As he puts it in On Acting, "The goddam play was telling me the style of the film" (270).

With the exception of Max Reinhardt's 1935 Midsummer Night's Dream, the preceding decade's Shakespeare films had been less stylistically innovative. Czinner's As You Like It and George Cukor's 1936 Romeo and Juliet don't look much different from the historical costume dramas made by the same studios. Even Reinhardt's Dream, which has tremendously creative dance sequences, looks very much like a Warner Brothers musical. By comparison, despite some similarities to historical costume dramas, Olivier's Henry V seems to have vaulted from the director's brain with its armor on its back.

Olivier recognized what he had achieved—"As far as I was concerned, Henry V might as well have been the first Shakespeare film"—yet by the time he was ready to make Hamlet he had come to regard his Henry as "kindergarten, end-of-the-pier stuff" (On Acting 267-68, 284). He resolved to go further with Hamlet, "to find a cinematic interpretation" that would "add to the universal consciousness of" the play (285, 286). Once again, he let the play determine film's style. He represented Hamlet's isolation from other characters with deep focus and his "feeling of alienation from the new court" with a camera that wandered "through the empty corridors, piercing the vast shadows of Elsinore's great rooms of state for some joy or the sight of some familiar object" (286).

The play may have determined which cinematic techniques Olivier used, but he had to get those techniques somewhere. Though in On Acting, he never says any film influenced him, I suspect that Citizen Kane inspired his use of deep focus. Any number of films might have inspired his use of a busy, roving camera for Hamlet's point of view. And any number might have influenced his use of bookend flashbacks. Citizen Kane, Wuthering Heights, and Double Indemnity all begin with their story's ends and then flash back to tell their tales until they reach what we saw in the beginning. But similarities between the openings of Rebecca and Hamlet suggest that Hitchcock's film directly influenced Olivier's.

Rebecca begins with fog winding through trees. After the credits, we hear Joan Fontaine, who plays the film's unnamed heroine, speak the opening words of Daphne du Maurier's novel: "Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again." As Fontaine's voiceover continues, we see the estate's iron gate. The camera takes us through the gate and up a driveway overhung with trees and overgrown with bushes until we see the ruins of Manderley manor. As in the novel, the film then moves to the beginning of the story. Olivier as Maxim de Winter looks down from a cliff at waves crashing upon jagged rocks, as if he's about to commit suicide.

|

Olivier as Hamlet does the same.

|

Olivier duplicates this shot when Hamlet contemplates suicide in the "To be or not to be" soliloquy. He also duplicates several features of Rebecca's opening. His Hamlet opens with swirling fog, a voiceover ("This is the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind"), and a shot from the end of the story: the prince's corpse on top of a castle tower. This shot dissolves into a shot from the story's beginning. We see the tower empty for a moment before we descend to watch Bernardo (Esmond Knight, who played Fluellen in Olivier's Henry V) climb the tower steps to start the play's first scene. At the end of the film, we return the tower, where we see Hamlet's body again.

Starting with a body and flashing back to tell the story of how it got that way is a familiar structure for mysteries; Sunset Boulevard and American Beauty are good examples. Oddly, I can find no films before 1948 that do this. The 1944 Mask of Dimitrios starts with a corpse but doesn't flash back, and the 1945 Mildred Pierce begins with a murder, not a corpse.

Could Olivier's Hamlet have been the first movie to flash back from a corpse? (Help me out with a comment if you know of any films before Olivier's that do this.)

Whether or not Olivier was the first director to flash back from a corpse in any movie, he was the first to do it in a Shakespeare movie. Two other great directors would follow his lead. Orson Welles begins his 1952 Othello with the funerals of Othello and Desdemona, with downward shots of their bodies that closely resemble Olivier's downward shot of Hamlet's. Welles's film then moves back in time to tell the story as one long flashback. Akira Kurosawa's 1957 adaptation of Macbeth also begins with a flashback. The film is known in English as Throne of Blood, but a more literal translation of the title is Spiderweb Castle, and Kurosawa opens with the castle's smoking ruins. Like Olivier's Elsinore and Hitchcock's Manderley, the ruins seem to emerge from fog. Kurosawa then lets the fog—or smoke—cover the castle before parting it to reveal an unburned castle and begin his story. We return to the ruins at the end of his film, just as we see Othello and Desdemona's funeral at the end of Welles's, and Hamlet's at the end of Olivier's.

|

Hamlet's corpse in the opening of Laurence Olivier's 1948 film.

Is this the first movie to open with a body and then flash back?

|

Other posts on Laurence Olivier's Hamlet: Freudianism, acting and cinematography, handling of the "To be or not to be" soliloquy.

Comments